Rollup 1/18 of the exhibition

The construction of the Penig subcamp

With regard to National Socialist forced labour in the Penig area, two sites are of central importance. On the one hand, there is the former Penig concentration camp subcamp, which was located between Penig and the village of Langenleuba-Oberhain and served to house former female forced labourers. On the other hand, the former Max Gehrt plant on Uhlandstraße in Penig must be considered, since forced labour had to be carried out there.

In 1944, the Penig facility of the raw products trading company Max Gehrt was converted into an armament’s enterprise. From then on, small aircraft components were produced there for Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG, whose headquarters were in Dessau. Whether, and to what extent, the company owners at the time were involved in this conversion, or whether it was ordered by National Socialist authorities, remains unclear to this day.

Because of the war, many German men of military age were serving as soldiers at the front and were therefore absent from the labour force. For this reason, in the summer of 1944 the plant commissioned plans for a barracks camp near a sand pit in Langenleuba-Oberhain, where forced labourers were to be imprisoned who had been assigned to work at the Max Gehrt plant.

Construction work to establish the camp finally began in August 1944; it comprised six barracks. From January 1945 onward, 703 female forced labourers were housed there, which amounted to severe overcrowding. The camp was secured by six guard towers and an electrified barbed-wire fence.

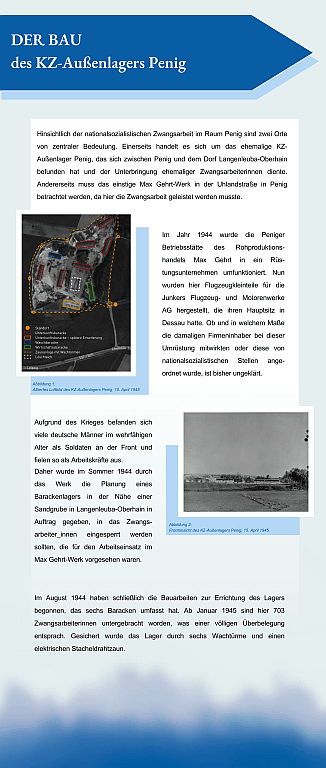

Figure 1: Allied aerial photograph of the Penig subcamp, 10 April 1945

Figure 2: Front view of the Penig subcamp, 15 April 1945